MOVIE REVIEW

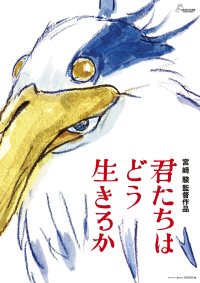

The Boy and the Heron (2023)

It would seem that, toward the end of their careers, Martin Scorsese (whose films are about greed and jealousy) and Hayao Miyazaki (whose films are about how to grow up) have swapped places. “The Boy and the Heron” is a depressing, out-of-place addition to a filmic legacy built around the importance of maturity to cope with life’s unpredictability. Since “Spirited Away” won the animation Oscar in 2001, Mr. Miyazaki’s movies have been widely anticipated around the world, including at the London Film Festival, while firmly maintaining their fiercely Japanese cultural aesthetic. However, it is inevitable that someone whose work is for children will end up repeating themselves, mostly because the core audience won’t notice. There’s not necessarily anything wrong with that, but “The Boy and the Heron’s” message is one of self-regard instead of self-belief, which curdles the entire plot into a sour mess.

The boy is Mahito (voiced by Soma Santoki); and the movie begins as, like “Bambi,” he loses his mother, to the Allied firebombing of Tokyo during the second World War. Some time after, his father (voiced by Takuya Kimura) takes him to the remote village where his mother was raised, where he has a munitions factory crucial to the war effort and married his late wife’s sister, Natsuko (voiced by Yoshino Kimura), who is pregnant. This is a lot for any grieving kid to deal with, so it’s no surprise that Mahito gets into fights at his new school and at his new home fixates on the heron which seems to be stalking him, appearing outside his window and generally being a nuisance. But it transpires that the heron is actually a disguised demon (voiced by Masaki Suda) who lets Mahito know that only someone of his bloodline can access the portals hidden in the nearby abandoned library-tower which becomes important when the lord of the tower (voiced by Shohei Hino), whose identity should not be spoiled, kidnaps Natsuko into another dimension.

Mahito shows a surprising amount of maturity – even more than Jennifer Connelly in “Labyrinth” – as he unhesitatingly crosses time and space to bring Natsuko home. The journey involves watching pelicans eat the souls of babies attempting to be reincarnated while a lady pirate (voiced by Kou Shibasaki) fights the flocks, a fire goddess (voiced by Aimyon) bringing Mahito to a world run by giant parakeets; and a final boss who looks remarkably like Dream from Neil Gaiman’s “The Sandman.” The dream logic is patently derivative but obviously works, but none of this is a dream, not even the unfortunate “bloodline” talk. On arrival in his new school Mahito is struggling so hard to adjust he self-harms, scarring his head with a bandage he must wear for half of his adventures, but this frightening and intriguing piece of characterization is sloughed aside by all the menacing talking birds. As war metaphors, or coping mechanisms for the loss of a mother, the birds just don’t land. And the trouble is, though the target audience won’t know it, Mr. Miyazaki has made better movies about war and loss of parents before.

So why this movie; and why this movie now? It would seem the great artist is trying to tell himself that everything over the course of his life has worked out for the best. All the lessons the women around him have worked so hard to teach him have enabled him to make exactly the right decisions; and the suffering inflicted by others and the control exerted on him by powerful, older men has been something he has defied. Mr. Miyazaki once gave an interview where he stated he made his movies for children who should not have been born. Depending on your point of view, this is either tremendously awful or tremendously kind. But the journey with “The Boy and the Heron” belongs to one boy alone; and the tone is somehow so cold and strange it’s hard to empathize. The residual goodwill for Mr. Miyazaki’s other films will no doubt ensure a receptive audience for this one, but little kids looking for a guide to adulthood would be better served by the rest of his work.

Comments