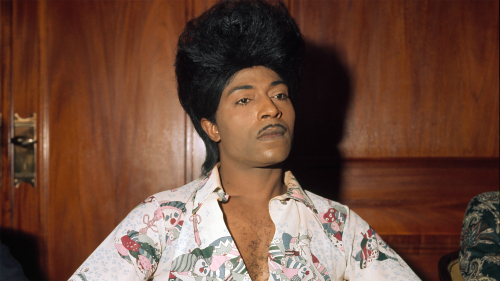

Courtesy of Sundance Institute

MOVIE REVIEW

Little Richard: I Am Everything (2023)

Baz Luhrmann's film "Elvis," already cooking at 450 Fahrenheit, is goosed even further when Alton Mason turns up playing Little Richard, screaming "Wop Bop-A-Loo-Bop" from a range of two inches as you rock backwards in your seat. Mr. Mason gives "Tutti Frutti" all he's got; but even skilled impersonations of Little Richard look like best guesses after 10 seconds of reminder about the real thing. This is handy for "Little Richard: I Am Everything," a documentary about the life and career of the singer born Richard Wayne Penniman, which samples a range of his performances but opts not to run any of them at length or let archive footage of the singer in action just unspool. The film wants to talk about the many contradictions and agonies in Little Richard the man, rather than the thermal updraft of the music; and for those issues, you have to hear him speak.

Little Richard speaking was always as much of a performance as him singing anyway. Lisa Cortés's film treats the exaggerations and hyperbole of the singer's high-glam patter as loveable showmanship, in preparation for taking them at face value: evidence that he felt exactly as aggrieved about his treatment at the hands of the musical establishment of the '50s and '60s and the musicians who pilfered his material as he always said he did. From the start it frames Little Richard as a protean queer man at a time when plenty of sexual play and drag performance and a few out gay musicians were in the cultural mix, even if confined to places that straight white people didn't register them. The singer dived into this pool with enthusiasm, and interviewees in the film testify to his influence as a beacon of nonconformity and release. The songs duly spread the word far and wide. When "Tutti Frutti" came on the radio no one with ears failed to spot that it was as filthy as sin and as free as the air, booting your parents' world of probity into the history books. Listeners in Timbuktu got the message.

Then the white establishment woke up and the problems started. Elvis Presley covering Little Richard songs is one thing, but when Pat Boone gives it a shot the machine is definitely after you. "Little Richard or Pat Boone is no contest, no matter what race you are," sighs John Waters in this documentary. Little Richard swerved in the other direction, joining the Seventh-day Adventist Church where his own music was a sin and offering to buy back his records from anyone looking to relieve themselves of the burden. The film follows him on this tangled path, through marriage, a wander back into secular showbiz again, a divorce, embrace of all the drugs, and a car crash. He became convinced that a raft of famous musicians had not acknowledged his influence upon them sufficiently. That he genuinely felt so is beyond question, although this kind of appropriation from Black music was already being caustically spoofed as par for the course by Eric Idle via The Rutles and "All You Need Is Cash" back in 1978.

Interviewees from Little Richard's circle of friends make his case for him, and Ms. Cortés doesn't cross-examine her celebrity contributors on the appropriation subject too deeply. She also leaves out layers of the subject's private life and for that matter his run-ins with the law. Sanitized is too strong a word, but by conjuring up a character of multiple extremes, the film is accidentally clear about which corners are not being ventured into. It wonders what the implications might be for the American mythology of rock music to say that the pioneers were Black queer people, without talking about Little Richard's male partners or gay love life to the same extent it discusses his period of heterosexual marriage and social influence. It presents Little Richard as "a man very good at liberating people and not so good at liberating himself," which has the shadings of tragedy, at least until the music restarts and tragedy seems the last thing on the cards.

Comments